As the taxi hailing behemoth encounters some serious bumps in the road, what does this latest drama reveal about our obsession with tech and convenience at all costs?

“While Uber has revolutionised the way people move in cities around the world, it’s equally true that we’ve got things wrong along the way. On behalf of everyone at Uber globally, I apologise for the mistakes we’ve made.”

The words of Uber chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi, who just a month into his role is fighting to keep his taxi hailing app firm alive in London.

In an open letter Khosrowshahi, who replaced scandal-hit company co-founder Travis Kalanick in August, said that while going forward Uber will not be “perfect”, it will listen to users, forge long-term partnerships in the cities it serves and run its business “with humility, integrity and passion”.

The charm offensive comes four days after news broke that Transport for London (TfL) will strip Uber of its licence to operate in the capital once it expires on 30 September, claiming the company is “not fit to hold a private hire operator licence”.

In a lengthy statement released on Friday TfL defended its decision, citing Uber’s failure to demonstrate “corporate responsibility” with regards to – amongst other things – its reporting of serious criminal offences and use of Greyball, shady software that blocks regulators from gaining full access to the app.

Uber now has less than 21 days to appeal the decision or pull out of London for good.

Winning (at all costs) mentality

Defeat is of course not an option for Uber. The tech giant is famously built on a macho culture of winning at all costs. Beneath the veneer of contrition it seems little has changed. Only on Monday London Mayor Sadiq Khan claimed Uber had put “unfair pressure” on TfL with its “army” of PR experts and lawyers.

These tactics come straight out of the Travis Kalanick handbook for disruptive business practices. Speaking once about his approach to taking on opposition, Kalanick is quoted as saying: “Stand by your principles and be comfortable with confrontation. So few people are, so when the people with the red tape come, it becomes a negotiation.”

The accusations of bad behaviour over the years are numerous. In August 2014, for example, Uber is alleged to have booked thousands of fake rides from competitor Lyft in an effort to hurt its profits and services. Then in February this year Google-owned self-driving car company Waymo filed a lawsuit claiming a former employee had stolen trade secrets for Uber.

Confrontation, aggression, sexism – all words associated with the toxic atmosphere at Uber’s San Francisco HQ. Sensing the tide of public opinion was turning, in June Uber fired 20 employees – including senior executives – following a sexual discrimination case filed by engineer Susan Fowler.

Fowler claimed she was propositioned for sex upon joining the company and encountered a culture where the shrinking number of females in the business was explained by the need for women to “step up and be better engineers”.

Out in the field, Uber’s treatment of drivers does not cast the taxi hailing firm in a better light. In fact TfL’s accusations of poor corporate responsibility relate in large part to the firm’s track record on drivers’ rights.

In December a report by Labour MP and chair of the work and pensions committee Frank Field, based on testimony from 83 drivers, described Uber as treating its drivers as Victorian-style “sweated labour”. Some drivers reportedly earn less than the minimum wage and work more than 70 hours a week just to make ends meet.

Uber’s willingness to operate in the grey area of the gig economy between self-employment and zero hours contracts has put pressure on drivers worldwide.

When confronted in March by an Uber driver struggling to make a living with the company’s declining rates, Kalanick was caught on camera slamming the driver for his lack of resourcefulness, claiming “some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit.” It was shortly after this that Kalanick finally admitted he needed “leadership help”.

Living in a bubble

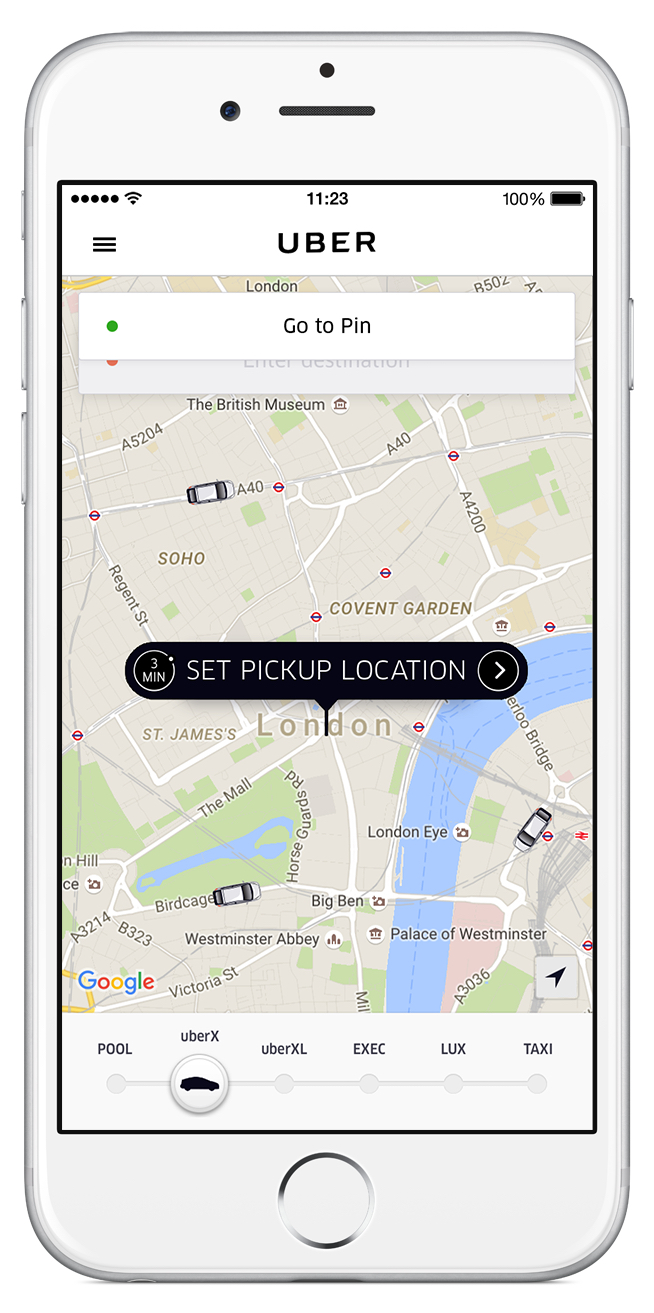

The sex scandals and poor driver conditions have, however, done nothing to dampen popularity for Uber. Our addiction to the seamless service of a taxi in your pocket has grown to such an extent over the past five years since Uber came to the UK that the prospect of waiting for a black cab, or hiring a mini-cab, feels borderline unthinkable.

The idea that Uber could be erased from the public’s consciousness without its consent has come as a shock to the system for many Londoners. In 2017 we are not used to having services or technology taken away from us. We have grown accustomed to bigger, better and faster – not slower, more expensive and harder to obtain. It goes against our idea of progress.

As a result the backlash to TfL’s decision to axe Uber has been swift. In his open letter Khosrowshahi said Uber will be appealing the decision “on behalf of millions of Londoners”. While millions might be a slight exaggeration, 680,000 people had signed an online petition to keep Uber operating in London as of Monday morning.

The palpable outrage felt by Londoners would not be mirrored across the wider UK should other authorities suspend the service. Step outside the London bubble and Uber does not have unlimited coverage nationwide. Despite focusing on key cities like Leeds, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow, if you live outside the urban centres Uber is not an essential part of daily life.

Far from it. In towns across the UK people are waiting for the council to fund a bus service that runs more frequently than once an hour or for their local train line to be electrified to stop the painful routine of daily cancellations. Worrying about hailing private hire taxis via apps is not really on their radar.

And that is the story of Uber. The haves and the have nots. Those who can buy cheap labour at the touch of a button. Those who live outside city centres and feel cheated by sub-standard public transport. Or even worse those who drive cars for 70 hours a week just to pay the crippling rents needed to live in one of the world’s most expensive cities.